The big chords guide for electronic musicians

Download this guide as free e-book.

Plus bonus content!

The full package contains this guide as 40 page PDF, an extra PDF with printable infographics, 20+ audio files, and 20+ MIDI files (chords and chord progressions for your own productions).

Welcome to the big free chords guide for electronic musicians. You have come to the right place if you want to know more about chords and how to use them in your own productions.

No previous knowledge is required. You neither need to be able to read notes from a note sheet, nor do you have to be a piano player to get the most out of this guide.

And you certainly don't have to be a music theory expert to understand the following chapters. But at the end of this guide you will surely know a lot more than before. This is what you will learn:

- How chords work and how you can use them in your productions.

- How different chord types sound (+ free ear training).

- Different ways to change the mood of your chords.

- How you can create nice chord progressions for your songs.

Ready for some action? Let's dive in!

Contents

- Why are chords so useful? The secret weapon for your song writing.

- So, what is a chord anyway?

- Ear training

- How the chord pages are structured

- Triads

- Four note chords

- So, what is a chord anyway? Part 2: Voicings.

- Voicing recipes

- Inversions and slash chords

- A quick look at advanced chords

- Chord progressions: How to string chords together

- A short introduction to scales

- The basic principle: Chords on scales

- Important chords of the Major scale

- Chord progressions of the Major scale

- Chord progressions of the Minor scale

- Chord progressions on other scales

- Advanced: Modal chord progressions and borrowed chords

- Other software tools for chords and scales

- Final words

Why are chords so useful? The secret weapon for your song writing.

It's easy to think that chords are just something that provides background flavour in your song. Like some lush pads or strings that fill the sonic space a bit.

But chords are so much more. They are not only useful to intensify emotions in your listeners. They can also help you to know exactly which notes you are allowed to play at any given time.

Do you know this problem? You wonder which notes you can use for your different instruments while your song evolves. You juggle around with various notes, try to make the instruments sound good together. Sometimes it works, sometimes it scares the hell out of your neighbours.

But behold! Chords are here for the rescue.

Here's the trick: If you start with the chords, your whole life will be easier. At least regarding the songwriting. If you know which chord notes you want to play, you also know which notes you can use for your bass lines, arpeggios, and background instruments.

The concept is very simple. A chord is made up of different notes that sound good together. Let's take the so called C Major chord for example. It consists of the notes C, E, and G.

If you choose a pad sound and play all these notes at once, you will create a flowing background atmosphere. Now choose another instrument. Maybe a piano. This time you don't play the chord notes at the same time, but switch between them every now and then. Simply pick a random note - C, E, or G - and jam around. Do the same with another instrument. And another.

Even though you may end up with dozens of instruments, they will always sound harmonic together. As long as you stay on the chord notes, nothing "bad" can happen.

Here's another trick. Pick a bass sound. Now always play on the deepest note of the chord (which is called "bass note", by the way). In our example this is the C. This note is perfect for bass lines, as the human ear already identified it as the lowest frequency in the spectrum of your background chords. Always play rhythmically on the deepest note of your chords and you will have an easy way to generate nice bass lines.

So, is this everything you have to do to write a nice song? Sometimes, yes. But in many cases it would be too boring if everything sounded harmonious from start to end. Good music finds a balance between predictability and surprises, harmony and tension.

However, there is an easy solution for that. In many genres there is a clear distinction between "background" instruments and a lead instrument. The lead instrument might be the voice of a singer, a guitar, a powerful synth, or anything else that cuts through the mix. This special instrument is not only allowed to play notes outside the chords, it is even encouraged to do so! These outside notes bring some tension to the song and make it more exciting.

When you work on the lead melody, you can always take a look at the current chord notes. Stick to these notes when you want to play it safe, stray away from them when you want to turn up the tension.

And always keep in mind: There are no fixed rules for music! If you want to go fancy with background melodies - do so! However, the concepts from above are a proven way to write songs that sound good and harmonious. And they work for many, many genres. From House to Metal. It can't hurt to know your chords!

So, what is a chord anyway?

A chord itself is a very simple thing: Take at least three different notes, play them together and you have a chord. Two notes aren't enough, as this is simply an interval (interval = the difference/distance between one note and another note).

However, although there are quite a few possibilities to form a chord, not all of them are common or useful. In this guide I will show you some of the most widely used chord types and how you can build them.

Each chord type has an own feeling or emotional quality that might be useful for your song. In this regard, there are no "good" chords or "bad" chords. They are either interesting for the atmosphere you want to create or not.

Each chord type can be created using a special recipe. This recipe will tell you which notes you need to stack together to build the chord.

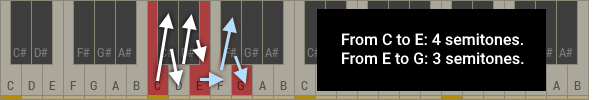

Let's work with an example. One of the simplest - and greatest! - chord types is the Major chord. It uses the following recipe:

- Start with any note (the so-called "root note").

- Add another note four semitones above the root note.

- Add a third note three semitones above the second note.

Let's create a C Major chord using this recipe. We take a look at the name: The "C" in "C Major" tells us which root note we need to take. We add four semitones and get an "E" as our second note (one semitone -> C#, two semitones -> D, three semitones -> D#, four semitones -> E). If we add another three semitones to the "E", we get a "G" as our third note.

The simplest types of chords are triads. Triads consist of three notes. They can sound very pure and harmonic (like Major and Minor triads) or full of tension (like Augmented or Diminished triads).

Four note chords are the next category. Many of them sound very nice as well, but even the most harmonic four note chord has more tension than the most harmonic triad. Due to the added note, the complexity is higher here. This can be very interesting for sophisticated chord progressions where triads might be too simple. On the other hand, four note chords might be too much for some styles. The choice is yours.

Ear training

It is important to develop a feeling for the different chord types. How they sound, which emotions they evoke, how they sound in comparison to each other.

There are several ways to do so:

- Play the chords on a real instrument, e.g. a piano.

- Listen to the accompanying soundfiles of this guide.

- Use the free software based Sundog training.

Obviously the piano technique is important for you, if you want to play these chords live one day.

However, if your main goal is electronic songwriting, then the other two ways might be even more interesting for you. After all, they are much quicker to utilize. And you don't need to twist your fingers to hear a sound.

Listening to the soundfiles of this guide is a good starting point to get a first impression of the chords. However, I highly recommend the third technique, because it has several benefits for electronic musicians:

- You can listen to the chords with a simple click of a button.

- You can not only listen to the chords, you can also connect Sundog to your DAW via MIDI. This way you can easily trigger chords in your DAW. So, it's not only an ear training, but also a useful production tool for you.

- While Sundog is a commercial product, the free Sundog demo contains everything you need to work with the chord examples of this guide.

- You can export chords and chord progressions as MIDI files. No need to build the chords from hand in your DAW (restriction: only two exports per demo session - unlimited in the full version).

Here is a short quickstart guide for you:

- Download Sundog at http://feelyoursound.com/download-sundog/ (Windows + macOS).

- Install it, then run Sundog.

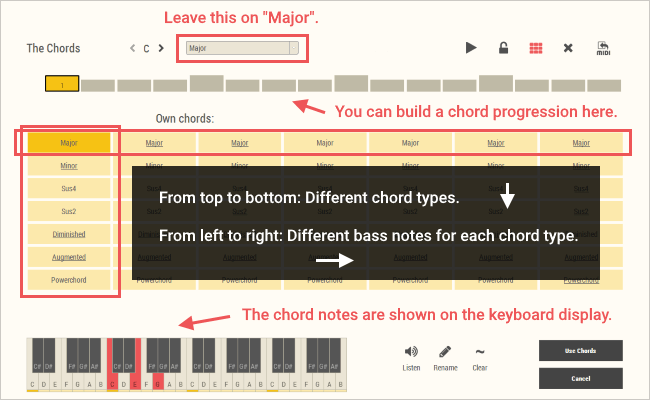

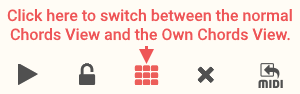

- Click on the "Chords" symbol in the red area.

- Important: Leave the scale settings on "Major". You can work with any basenote though (C, C#,..).

- Now click on "Chords -> Load own chords..." and choose "major_-_triads.oc".

- Hooray! You can click on the buttons to listen to the chords now.

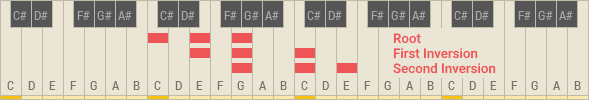

The following image shows a screenshot of Sundog. Each row contains one chord type. And each column starts with the same bass note.

Sundog contains a built-in preview synth. But you can also connect it to your DAW via MIDI. Some setup guides can be found here:

http://www.feelyoursound.com/sundog-manual/#setup

How the chord pages are structured

The following pages will show you the most important chords. We start with triads and then continue to the four note chords (also called "tetrads").

Each section contains the following parts:

- Chord name.

- Popular abbreviation.

- Construction recipe with semitones.

- Emotional effect / atmosphere.

- Example chord with image.

- An audio file with several chord examples of varying pitches.

The free download version of this guide contains a printable infographic (PDF) with all chords as well.

A note on chord names: Don't let the names intimidate you! You only need to know how you can build these chords and how they sound. And this is really easy. The chord names will become important if you want to talk to other musicians. Or if you need to read about some new songwriting techniques. After all, you can always take a quick look at this guide. So don't fear the names!

Triads

Sundog ear training: Go to the Chords Page, click on "Chords -> Load own chords...", and open "major_-_triads.oc".

Major

Abbreviation: maj

Construction: 0 - 4 - 3

Atmosphere: Happy, bright, satisfied, stable

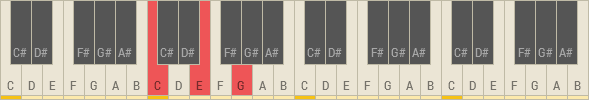

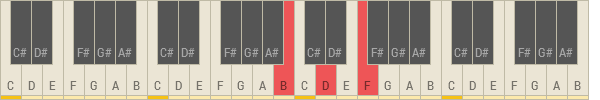

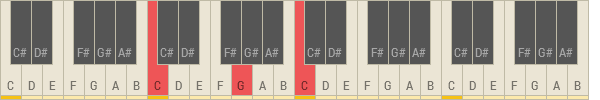

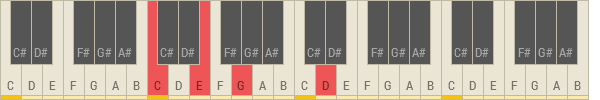

Example: C Major / Cmaj (C - E - G)

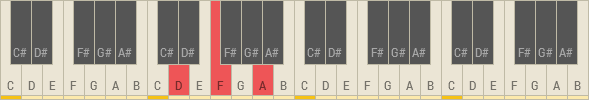

Minor

Abbreviation: min

Construction: 0 - 3 - 4

Atmosphere: Sad, dark, melancholic, mysterious, serious

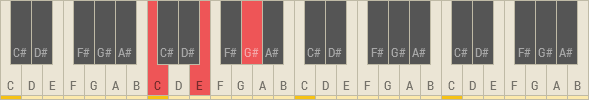

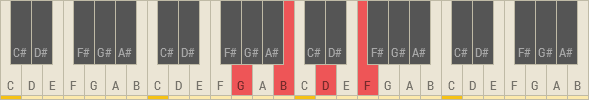

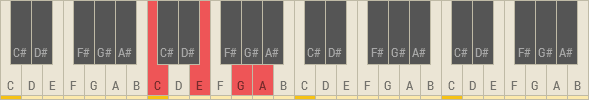

Example: D Minor / Dmin (D - F - A)

Diminished

Abbreviation: dim

Construction: 0 - 3 - 3

Atmosphere: Spooky, fearful, doomed

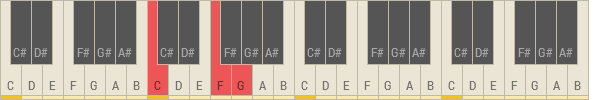

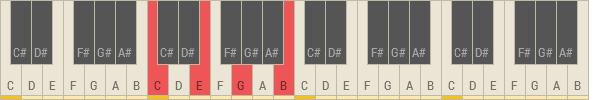

Example: B Diminished / Bdim (B - D - F)

Augmented

Abbreviation: aug

Construction: 0 - 4 - 4

Atmosphere: Disharmonic, suspenseful

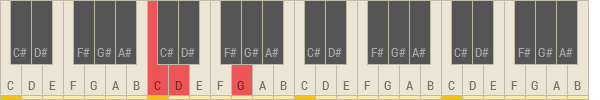

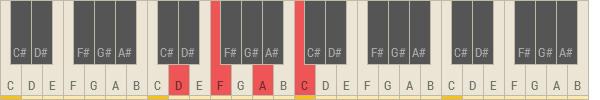

Example: C Augmented / Caug (C - E - G#)

Suspended Fourth

Abbreviation: sus4

Construction: 0 - 5 - 2

Atmosphere: Tension, majestic

Example: C Suspended Fourth / Csus4 (C - F - G)

Suspended Second

Abbreviation: sus2

Construction: 0 - 2 - 5

Atmosphere: Tension, majestic

Example: Csus2 (C - D - G)

Powerchord

Abbreviation: 5

Construction: 0 - 7 - 5

Atmosphere: Powerful, forceful

Example: C-Powerchord / C5 (C - G - C)

Note: Powerchords aren't "real" chords by definition. As you can see, the "chord" consists of only two different notes. But powerchords are so common in certain genres that I include them here as well. Powerchords need some kind of distortion to come to life.

Four note chords

Sundog ear training: Go to the Chords Page, click on "Chords -> Load own chords...", and open "major_-_four_note_chords.oc".

(Dominant) Seventh (aka Major Minor Seventh)

Abbreviation: dom7 or 7

Construction: 0 - 4 - 3 - 3

Atmosphere: Powerful, forceful

Example: G Dominant Seventh / G7 (G - B - D - F)

Note: The Dominant Seventh plays two important roles within Western music.

1) The character and the tension of this chord are so strong that the listener craves for a resolution. This is the reason why the Dominant Seventh is the perfect chord to go back to the tonic of the current scale (please read later chapters).

2) As this urge is so strong, you can also use the chord to modulate to another scale. To do this, you pick a Dominant Seventh from another scale and then play the tonic of the new scale directly after that.

Major Seventh

Abbreviation: maj7

Construction: 0 - 4 - 3 - 4

Atmosphere: Smooth, soft, jazzy, calm, thoughtful

Example: C Major Seventh / Cmaj7 (C - E - G - B)

Minor Seventh

Abbreviation: min7

Construction: 0 - 3 - 4 - 3

Atmosphere: Smooth, jazzy, mellow, contemplative

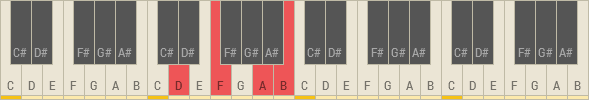

Example: D Minor Seventh / Dmin7 (D - F - A - C)

Added Ninth

Abbreviation: add9

Construction: 0 - 4 - 3 - 7

Atmosphere: Energetic, bright

Example: C Added Ninth / Cadd9 (C - E - G - D)

Major Sixth

Abbreviation: 6

Construction: 0 - 4 - 3 - 2

Atmosphere: Fun, playful

Example: C Major Sixth / C6 (C - E - G - A)

Minor Sixth

Abbreviation: min6

Construction: 0 - 3 - 4 - 2

Atmosphere: Dark, mysterious

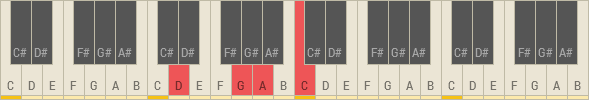

Example: D Minor Sixth / Dmin6 (D - F - A - B)

Seventh Suspended Fourth

Abbreviation: 7sus4

Construction: 0 - 5 - 2 - 3

Atmosphere: Tension

Example: D Seventh Suspended Fourth / D7sus4 (D - G - A - C)

So, what is a chord anyway? Part 2: Voicings.

In the last chapters I told you how you can create some nice chords for your songs.

But I didn't tell you the whole story. Yet.

Chords have one primary function in your song. They provide the background paint for everything else. As I told you in the first chapters, the chord notes are important, because they tell you which melody notes are a good fit and which are not.

In this regard it doesn't matter whether your background chord is played with the notes "C3 - E3 - G3" or with the notes "E3 - G3 - C4". Both variations serve the same purpose: The notes C, E, and G are chord notes, the other notes are not.

And not only this. The two variations share the same name. They are both C Major chords. As you have learned, a Major chord is constructed using the formula "0 - 4 - 3". Do the math and you will see that C Major contains the notes C, E, and G.

Chords that have been built this way are playing in so-called "close root position". In this position the root note ("C") is identical to the lowest note of the chord (the "bass note").

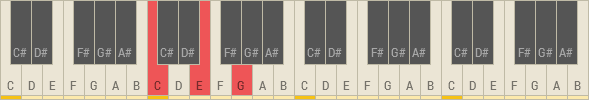

But you can always rearrange the notes in any way that you like! The different variations are called "voicings". Take a look, all these chords are C Major voicings:

Why would we want to do that? Well, although the harmonic function of these voicings is the same, they all sound a bit differently.

While the chord types have an emotional quality of their own, the different voicings are another way to alter the mood of your song.

Voicing recipes

Here are some common voicing techniques and their emotional effects. You can always mix these techniques and build some more complex variations.

Sundog ear training: Go to the Chords Page, click on "Chords -> Load own chords...", and open "major_-_chord_variations.oc".

Name: Closed chord

Concept: All chord notes are as close together as possible. This is the standard position of any chord.

Quality: The sound is very focused, but also a bit tense.

Name: Open chord

Concept: Take the second note of your chord and put it one octave above instead.

Note: This will open up the sound quite a bit. The new chord will sound much more airy and spacious. This technique is very common in many Trance songs. You can also use a different note than the second, but the second note is a very common candidate for this technique.

Name: Doubled bass

Concept: Copy the lowest note of your chord and put it one octave below as well.

Note: This is a good way to add some weight to the chord. An instrument that is played like this is much more powerful. However, it might also be difficult to do a proper mix with it, because the instrument covers a wider frequency range then.

Advanced tip for Sundog users: Sundog contains a built-in way to create voicings on the fly. Please read http://www.feelyoursound.com/sundog-manual/#chordmods for more information.

Inversions and slash chords

In the first chapters I wrote about the great benefits that you get when you start with the chords. One such benefit is that you always know which notes you may play with your bass instrument. Simply work on the lowest note (bass note) of your chord and you are good to go.

The highest note is interesting as well, because it can be identified by the ears of your listeners as the note with the highest melodic impact. When you play several chords after each other, the highest notes will form a (weak) little melody by themselves. Sure, your instruments will need some extra work to make this melody shine, but compared to the second note, the highest note is the prima donna.

So, what happens when your chords are interesting for their harmonic qualities, but they don't sound good when you want to use them for your bass lines?

This is where inversions come into play.

Inversions are a special kind of voicing that are very, very common when you need to rearrange your chords a bit. The concept is actually very easy. Instead of the root note, a different note is in the bass. Other than that, the notes are still as close to each other as possible.

To create the so called "first inversion", you need to move the root note one octave higher. Now the second note is in the bass.

Example: We begin with a C Major chord in root position. The notes are C3, E3, and G3. Now move the root note one octave up and we get the first inversion: E3, G3, C4. As you see, E3 is in the bass now.

The second inversion builds upon the first inversion. We do the same trick again: Move the lowest note one octave higher, so that a different note is in the bass.

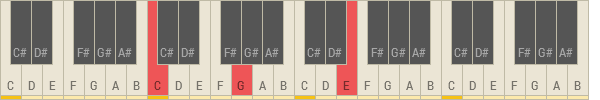

Example with C Major:

- Root position: C3, E3, and G3 (root in the bass)

- First inversion: E3, G3, C4 (second note of the original chord in the bass)

- Second inversion: G3, C4, E4 (third note of the original chord in the bass)

Of course you can transpose the inversions one octave down, if the final chord is too high now.

Apart from the bass line trick, there is another popular reason why musicians use inversions. Imagine that you are a pianist. You play some nice chords with your left hand and a beautiful melody with your right hand.

You have a lot to do, so you want to move your left hand as little as possible. If the chords were jumping too much up and down, you would lose track too quickly. This is when inversions are used. The change from one chord to the next one is chosen in such a way, that as few fingers are moved as possible.

A little Sundog trick for you: When you are on the Chords Page, you can press the up/down arrow keys on your keyboard to invert the current chord.

Inversions are frequently notated using the "slash chord" format. First, you write down the name of the chord, then you add a slash ("/"), and finally end with the bass note.

Example: The first inversion of C Major uses the notes E3, G3, C4. This is notated as "Cmaj/E".

Please note that this format is also used for chords that work with a bass note which isn't part of the chord at all. Example: "Cmaj/A" is a standard C Major chord (C, E, G) which uses an additional "A" as its bass note.

A quick look at advanced chords

Apart from the triads and four note chords of this guide, there are also quite a few advanced chords.

Many of them use more than four notes and are especially interesting for Jazz and related genres.

I won't go into the details here, because I think that in most cases the "standard" chords are more than enough. So, feel free to skip this chapter if you like.

But if you really want to get fancy, I would recommend to take a look at the so called "extended chords".

The most important extended chords are the 9th, the 11th, and the 13th. The numbers refer to the amount of scale steps you need to take to reach another note for your chord.

Example:

- We work on the C Major scale: 1 = C, 2 = D, 3 = E, 4 = F, 5 = G, 6 = A, 7 = B, 8 = C, 9 = D, 10 = E, 11 = F, 12 = G, 13 = A

- We want to create a Cmaj9 chord.

- Let's start with a standard Cmaj7 chord: C, E, G, B

- We add the 9th step on the scale, starting from our root note. We end up with C, E, G, B, D.

- Now let's create a Cmaj11 chord.

- Cmaj11 is a Cmaj9 chord plus another note at the 11th step.

- This results in the notes C, E, G, B, D, F.

- Cmaj13 is a Cmaj11 plus the 13th step: C, E, G, B, D, F, A.

- As you can see, Cmaj13 contains all the notes of the scale. You can't get more fancy than that ;).

- Please take care to always work with steps on the scale, NOT positions on the scale. This is NOT a Dm9 chord: D, F, A, C, D. THIS is a Dm9 chord: D, F, A, C, E.

Chord progressions: How to string chords together

We concentrated on single chords and their effects so far. However, in reality you will hardly find any chords in isolation. But how do you find chords that sound good together? And can you take any chords that you like? Or are there some rules that will make your life easier?

To make it short: No, you cannot take any two or more chords and simply string them together. At least the chances are very high that you will create a mess this way.

There are at least seven basic triads and seven basic four note chords. Combine this with the 12 different notes of the octave and you end up with 168 possible chords - and we didn't even count in the inversions yet.

Does this mean that all hope is lost? Fortunately not!

The following chapters will show you the basic chord progression principle behind nearly every big Western music genre. Be it pop, rock, trance, RnB, or folk music.

A short introduction to scales

Let's forget about chords for a while and take a look at one of the other cornerstones of music: Scales.

Basically, scales are a collection of notes that "sound good together". You can use them to create a certain atmosphere in your song. Instead of juggling around with all twelve notes of the octave, you just concentrate on a few of them. This makes it way easier to find nice melodies.

The two most important scales of Western music are called the Major and the Minor scale. The Major scale is mostly used for happy, upbeat songs. The Minor scale is more interesting for thoughtful, sad, serious songs. More than 80% of modern electronic tracks use the Minor scale.

As I said, a scale is a collection of notes. But each collection contains one note that is especially important. This note is called the root note of the scale (not to be confused with the root of a chord!).

Starting from the root, each scale has a special mathematical recipe how you construct the rest of the notes. For example, the Major scale is built like this:

- 1st note = Root note

- 2nd = Root note + 2 halftones

- 3rd = 2nd + 2 halftones

- 4th = 3rd + 1 halftone

- 5th = 4th + 2 halftones

- 6th = 5th + 2 halftones

- 7th = 6th + 2 halftones

Let's take a look at C Major. Apply the recipe to "C" and you will see that C Major consists of all the white notes on the keyboard.

The basic principle: Chords on scales

But what does this have to do with chords?

Well, scales - especially the Major and the Minor scale - are not only interesting for melodies, they are also a great way to find good chords for your song.

Here is the basic idea. Instead of using all possible variations, you only work with those chords where all notes are part of the scale (so-called "diatonic" chords). This way you can guarantee that you work with a central theme. Your listeners will feel that there is a connection between your chords and your melodies.

So, basically you will need to go through all the different variations and see if each note is on the scale. Or you can do yourself a favour and use one of the free pre-built chord tables at http://feelyoursound.com/scale-chords/. Subscribers of the FeelYourSound newsletter can also download a free BIG pack of infographics and MIDI files for over 300 scales.

For example, here are all the chords for C Major:

http://feelyoursound.com/scale-chords/c-major/

Using the scale-chords-overview is a nice way to catch a first glimpse of the possibilities that you have.

But there is an even better trick. One of Sundog's core features is the automatic calculation of matching chords for each scale. If you connect Sundog to your DAW, you will have every chord right at your mouse pointer.

Here is a quick run-through:

- Start Sundog.

- Click on the Chords icon.

- Choose a scale and a base note.

- Now Sundog will show you all the matching chords.

- Click on the buttons to hear and see the notes. Do a right-click to transpose the chords one octave lower.

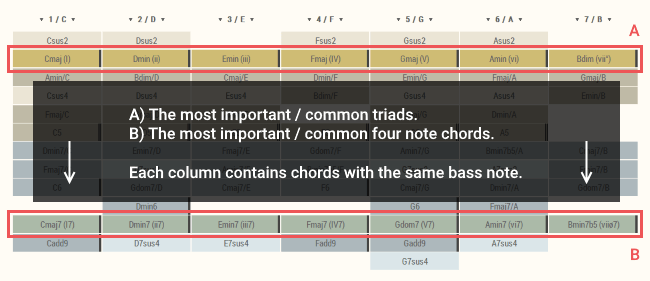

Side note: If you have worked with the chord collections of earlier chapters so far, you will need to switch between the Own Chords View and the normal Chords View. You can toggle between these views with the icon to the right of the lock symbol:

Important chords of the Major scale

The Major and the Minor scale are the most commonly used scales in Western music. They are not only popular for their nice melodic intervals, but also for their chords.

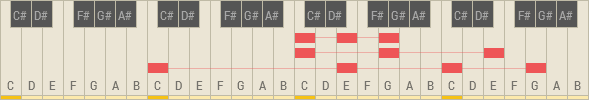

Take a look at the Sundog Chords View of C Major:

As you can see, each column contains chords with the same bass note. And not only that!

There are two special rows that contain only chords in close root position (boxes A and B). This is a highly remarkable characteristic that makes the Major scale very interesting for songwriting. In many other scales you won't have the opportunity to find close root chords for each available note.

For starters, I highly recommend to use the chords of the boxes A and B exclusively. They will give you plenty of opportunities to build nice progressions, and many great songs have been written with these standard chords alone.

In fact, these chords are so important that musicians invented an own notation for them. It goes like this:

- Each note of the scale gets a number, starting from one.

- Roman numerals are used to name the chords.

- Major chords -> capital letters. Minor chords -> lower case letters. Four note chords end with a "7".

For C Major, this results in the following table:

- 1 = C -> Cmaj (I) and Cmaj7 (I7)

- 2 = D -> Dmin (ii) and Dmin7 (ii7)

- 3 = E -> Emin (iii) and Emin7 (iii7)

- 4 = F -> Fmaj (IV) and Fmaj7 (IV7)

- 5 = G -> Gmaj (V) and Gdom7 (V7)

- 6 = A -> Amin (vi) and Amin7 (vi7)

- 7 = B -> Bdim (vii°) and Bmin7b5 (viiø7)

"OK great", you think, "but what's in it for me?".

Well, one of the biggest advantages of this notation is the fact that you can describe chord progressions pretty easily this way.

It doesn't matter which root note you use for your scale. A "I - V" chord progression in C Major has the same function and feeling like a "I - V" progression in F# Major. The latter has been transposed a few semitones higher, that's all. The C Major "I - V" uses the chords Cmaj and Gmaj, whereas the F# Major version uses F#maj and C#maj.

Chord progressions of the Major scale

Restricting yourself to the 14 standard chords is a good way to increase the chance that you will end up with a nice chord progression. But there are a few other tricks that will make your life easier.

First, let's talk about the so-called "tonic chord". This is the name for the first chord of the scale. The tonic is extremely important for your songwriting, because it will help you to show your listeners which scale you are using.

If you don't make it crystal clear to your listeners which scale you use, they will constantly have a feeling that something "isn't right" yet. As with everything in music, this might be a desired effect. But in many cases you want to be as clear as possible here.

Let's take a look at the A Minor scale. It consists of the notes A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. Whoopa! These are the same notes as those of the C Major scale. What's going on here?

Well, the Major and the Minor scale are related to each other, but due to the different root notes they sound differently. The order of the intervals is the important point. When you start to play on the A and then move up, you work with different intervals than when you start from the C.

The tonic of the A Minor scale is the A Minor chord. The tonic of the C Major scale is the C Major chord. As you can imagine, the fact that the two tonics have such different harmonic qualities will help your listeners to intuitively decide which scale you work on.

The best position to use the tonic is at the beginning and/or the end of your progression. The first option has a "starting the journey" effect, the second option feels like "coming back home".

Another important chord of the Major scale is the V chord (and also its four note variation V7). Take a look at the V in isolation and you will see that it's just a simple Major chord. But when the listener is tuned in on the notes and intervals of the scale, the V becomes something special.

As soon as the listener is in tune, he automatically "compares" each chord note with the base note of the scale. Such a comparison happens subconsciously of course.

Let's take a look at the notes of the V chord in the C Major scale. Gmaj consists of the notes G, B, and D. As I said before, the brain of the listener compares each note with the tonic (C). The distance between B and C and D and C is so small (1 semitone and 2 semitones), that you won't find any chord that builds up more tension. And as you know, tension wants to get released!

Because of this need for relief, the V chord is the perfect candidate if you want to drive a chord progression home to the tonic. This is the reason why countless songs contain a "V - I" progression in the end of a section.

There are several common theories how chords of the Major scale relate to each other and why this is the case. I won't go into the details here, but one of the most important driving factors is the interval between the root notes of the different chords. If you want to find out more, I recommend a search for "chord circle progression" / "circular progression" / "root motion" / "root note movement".

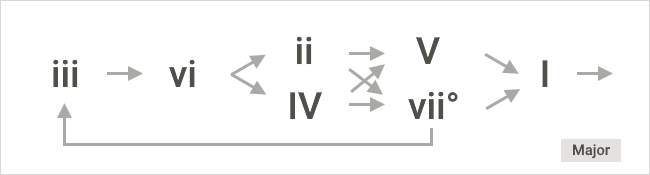

However, for this guide it's more important that you can build nice chord progressions quickly. Without further ado, here is a diagram for quick and easy Major scale chord progressions:

A few remarks:

- The "I" chord is like a joker. You can go to any other chord from here.

- The chart lists only triads. But four note chords work essentially the same.

- The chord motions are just suggestions. You don't NEED to follow this chart at all.

And another hint: Sundog contains 500 common Major scale chord progressions, ordered by popularity. You can use them to get a feeling for typical 4-bar progressions. Simply go to the Chords View, then click on "Chords -> Search chord progression" in the menu.

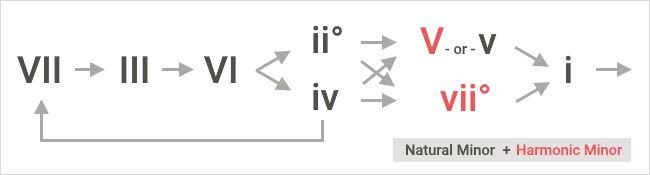

Chord progressions of the Minor scale

Before you read the following paragraphs, please make sure that you have read the sections about the Major scale. Especially the stuff on tonics, Roman numerals, and the importance of the V chord.

The Minor scale is the other important scale of Western music. While many pop and rock songs use the Major scale, more than 80% of the electronic music styles prefer the Minor scale.

An easy example for a Minor scale is "A Minor". It consists of the white keys of the keyboard, starting from A.

The most comfortable way to create chord progressions here is simply this:

- Only use chords where all notes are part of the scale.

- Use the tonic chord to make clear on which scale you are. Preferably at the start or end of your progression.

Many people use the Minor scale exactly like this. And that's absolutely fine for many songs.

However, there is one problem. And this problem is linked to the importance of the V chord. On the Major scale the V chord creates such a strong pull to the tonic that you can hardly escape it.

As I explained before, the second and the third note of the chord are only one and two semitones away from the tonic of the Major scale. Especially the interval of just one semitone creates a strong feeling of tension. And this tension is resolved by moving on to the all-important tonic chord.

Now let's take a look at the fifth chord of the Minor scale. The Roman numerals are:

i - ii° - III - iv - v - VI - VII

The "v" of "A Minor" consists of the notes E, G, B. The interval from G to A is two semitones, and the interval from B to A is two semitones as well.

Bummer! It would be so nice if we could work with a major "V" chord as well here. "E Major" consists of the notes E, G#, and B. This would be perfect to create the same tension as on the Major scale. But unfortunately the G# lies outside the scale.

There are two different solutions for this:

1) Temporarily "borrow" the V chord from the related Major scale.

2) Change the construction of the scale, so that we can create a Major chord instead of a Minor chord at the fifth position.

Both solutions are commonly used. The first one is self-explanatory: Whenever you want to create a strong pull to the tonic, use a "V" instead of a "v". Everything else remains the same.

The second solution is interesting as well. The "standard" version of Minor is constructed like this (notation using semitones):

0 | +2 | +1 | +2 | +2 | +1 | +2

In "A Minor", this results in the white keys: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.

Now let's change the scale formula in such a way that we end up with A, B, C, D, E, F, G#:

0 | +2 | +1 | +2 | +2 | +1 | +3

As you can see, this is the same formula as in the standard Minor version, but the last note is raised by one semitone. The standard Minor is called "Natural Minor", this one is called "Harmonic Minor".

The Roman numerals are:

i - ii° - III - iv - v - VI - VII (Natural Minor)

i - ii° - III+ - iv - V - VI - vii° (Harmonic Minor)

The third, fifth, and seventh position have changed, the rest remains the same. We already talked about the V, but the vii° is interesting as well.

The first and the second note of the vii° chord (which is a Diminished triad, by the way) are just one and two semitones away from the tonic of the scale. For this reason the vii° creates a similar tension like the V chord. However, the aural character of the Diminished chord is not as pleasing as that of a Major chord for example, so it's not as commonly used.

Truth be told, the third position of the Harmonic Minor is a bit disappointing. We traded in a solid Major triad for an Augmented chord. Yes, there might be some situations where this could be interesting, but in many cases we would rather stick to the Major chord here.

All the arguments and thoughts from above are the reason why Minor scale chord progressions seem to be a bit harder to handle than Major scale progressions.

But fear not. You can always work just on the standard chords of the Natural Minor scale. It's not wrong to do so, it simply means that in some cases you could create even stronger chord progressions by choosing chords outside the scale.

Chord progressions on other scales

The Major and the Minor scale are the most important scales if you want to work with chords. Compared to many other music cultures, Western music relies quite heavily on chords and chord progressions.

If you want to compose music on other scales, please be aware that in many cases the desired effect won't come from great chord progressions.

For example, quite a few other traditions use drone sounds to establish tonality. Drone music plays one note - often the root note - throughout the whole song (or at least large parts of it). This note can be sustained or repeated. A classic example is bagpipe music.

If you want to take a quick look at the possible chords of many different scales, you can either use the free Scale Chords project at http://feelyoursound.com/scale-chords/. Or you can use the full version of Sundog.

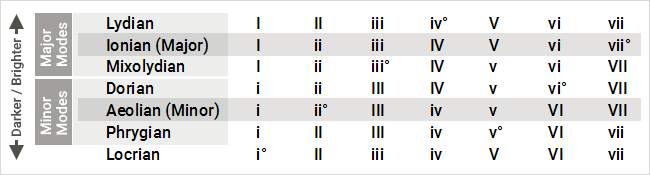

Advanced: Modal chord progressions and borrowed chords

I already told you about the Major and the Minor scale and that they are related to each other. For example, "C Major" and "A Major" both use the white keys of the keyboard, but they start at different note positions.

Surprise, surprise: There are five other scales that are part of the same family. The whole collection is called "the seven Western modes". Each of these modes has got an own flavour.

A word of caution before I continue: When you start out, it's better to use the Major and the Minor scale exclusively for a while. In fact, these two are used more often than the other modes combined. It's a good idea to develop a feeling for Major and Minor before you start to work with the other modes. You really need to make clear in which mode you are, as your listeners will get confused otherwise.

Oh, and by the way: It's perfectly fine to stick to Major and Minor! You have plenty of options to write interesting songs there.

This being said, let's start with a small overview. There are seven different modes. Their character ranges from bright to dark. Three of them are considered to be "Major modes" (their tonic is a Major chord), three others count as "Minor modes" (the tonic is Minor), and one is a "Diminished mode". The latter is only rarely used, because the tonic doesn't sound very pleasant.

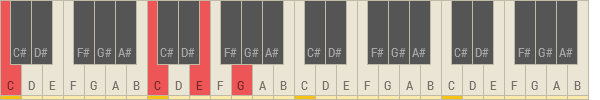

The Ionian mode is identical to the Major scale, the Aeolian mode is identical to the Minor scale. The following image lists all the chords of the seven modes:

But how do you write good chord progressions in other modes than Ionian (Major) or Aeolian (Minor)?

As with the Major and the Minor scale, using the tonic chord is extremely important here. The tonic chord establishes the home base of your song. You can position it at the beginning and/or the end of your progression.

The second important ingredient is a chord that leads to the tonic chord. This chord should be exclusive or at least very characteristic for the chosen mode.

Example: We want to write a chord progression in Dorian. We start with "i", then follow up with "III" and "VII". The "i", "III", and "VII" are also available in the Minor scale. We need another last chord now that is only available in the Dorian mode. Otherwise our listeners would think that we created a standard Minor scale chord progression here. A quick look at the chart above reveals that we could use a "IV" chord. The Minor scale works with a "iv", so "IV" is a nice way to point our listeners to the Dorian mode.

But there is also another interesting technique to enhance your songwriting possibilities. It is called "modal interchange".

Modal interchange happens when you "borrow" a chord from a parallel mode (parallel: both modes start on the same key). Usually you only work with chords where all the chord notes belong to your chosen scale/mode. However, from time to time it might be interesting to surprise the listener with a chord from outside the scale.

Many songwriters use this approach when they work on the Major or the Minor scale. They pick one of the two scales and then borrow a single chord from the other scale to spice things up.

Let's take a look at the chords again:

- Major: I - ii - iii - IV - V - vi - vii°

- Minor: i - ii° - III - iv - v - VI - VII

The following chord progression is an example for modal interchange:

I - V - vi - IV - iv

As you can see, the first four chords are from the Major scale, the last chord is borrowed from the minor scale. And it gives the whole progression a nice edge.

A little warning: Please use this technique sparingly, because otherwise it will be near impossible to establish a common ground for your song. In many cases, borrowing just one chord is more than enough.

Other software tools for chords and scales

At FeelYourSound, I specialize on tools for electronic songwriting. The software that I create is meant to assist you in your quest for nice chord progressions, bass lines, and melodies.

You already know Sundog, but there are two other tools that might be helpful for you as well:

XotoPad is designed to turn any Windows tablet into a flexible MIDI touch controller. The app is especially useful for sketching chord progressions and playing around with melodies. Over 300 scales are included to build own scale keyboards and chord pages within seconds. Other features: GM drum maps, isomorphic layouts, MIDI sliders, faders, XY-controllers, CC switches, full screen mode, "always on top" mode, and much more. More info here: http://feelyoursound.com/xotopad/

MelodicFlow is a MIDI performance and songwriting VSTi for Windows and macOS. MelodicFlow will bend the upper white keys of your keyboard in such a way that they will always sound harmonic to your chords. You can also use MelodicFlow to become a fluent scale player instantly. Over 300 scales are included, and you only have to play the white keys to use them. More info here: http://feelyoursound.com/melodicflow/

Final words

I hope you liked this guide and found it useful for your own songwriting. Please share it with your friends if you know someone who could benefit from it (but please don't copy the content and put it on another website without my permission).

If you like to reach out to me, you can do so at http://feelyoursound.com/contact/.

I wish you a lot of success with your productions!

Cheers,

Hauke of FeelYourSound